Guide to Underwater Archaeology

Guide to Underwater Archaeology

“The major obstacle facing us was lack of time, for we had an hour or less daily, in two dives, at the depths in which we worked. We needed more efficient methods.”

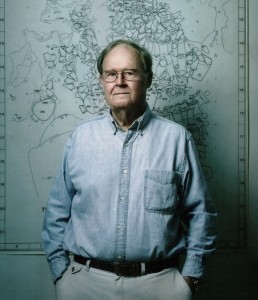

–George F. Bass

The Development of Techniques

BY GEORGE F. BASS

Although it was the early date of the Bronze Age shipwreck at Cape Gelidonya, Turkey, that attracted me to underwater archaeology in 1960, it was the challenge of overcoming some of the problems we faced that enticed me to continue throughout the 1960s, on Byzantine and Roman wrecks at Yassi Ada, Turkey. The major obstacle facing us was lack of time, for we had an hour or less daily, in two dives, at the depths in which we worked. We needed more efficient methods.

Although the French pioneers of working on ancient wrecks had already used air lifts (suction pipes) for removing sediment, and air-filled bags for raising heavy items, and Italians were covering their wrecks with rigid metals grids to aid mapping, we experimented with plane tables and other mapping devices, recording measurements on sheets of frosted plastic (Mylar) with ordinary pencils. We then used horizontal metal grids as the bases for movable photographic towers from which we mapped the sites. Because that was still too time-consuming, I invented a system of mapping three-dimensionally with stereo-photographs, and then, with a U.S. Navy grant, adapted that method for use from our two-person Asherah, launched in 1964 as the first commercially built American research submersible. Today, however, all of these mapping methods have been superceded by a combination of digital photography and various computer programs that allow a single diver to record a site as it is excavated.

Michael and Susan Katzev made diving safer by designing an underwater phone booth, an air-filled acrylic hemisphere in which a diver can stand, dry from the chest up, and talk either to the surface by telephone or directly to a partner, or change failed equipment without surfacing. In addition, we began to breath pure oxygen at the last decompression stop to speed the discharge of nitrogen from our bodies. Soon after, off Cyprus, Michael showed that light, plastic irrigation pipes made more efficient air lifts than the unwieldy metal air-lifts used universally until then.

Although ours was the first team to locate an ancient wreck with side-scan sonar, in 1967 in Turkey, and off Jamaica we have since found early wrecks both with sub-bottom profilers, or sonars that look beneath the seabed, and magnetometers, which detect iron, our two-person submersible Carolyn has revolutionized surveys in the depths in which we can excavate. Of course we can now record exact positions of newly discovered sites with portable GPS units instead of taking land bearings, or by simply describing the nearest terrain as we once did.