Hi There!

The Texas A&M University, Institute of Nautical Archaeology and Lake Champlain Maritime Museum (LCMM) crew is back to work for a third season at the Shelburne Shipyard in Lake Champlain, Vermont. The Shelburne Shipyard Project is an ongoing project co-directed by Dr. Kevin Crisman and Carolyn Kennedy (me) since 2013, its first field season taking place in June of 2014. Each year, Crisman and Kennedy have brought a team of nautical archaeology students from Texas to Vermont to record shipwrecks in the natural harbor at the northern end of Shelburne Point that was chosen as the shipyard location for early Lake Champlain passenger steamboat companies due to its natural protection from the prevailing winds on the lake (Fig. 1).

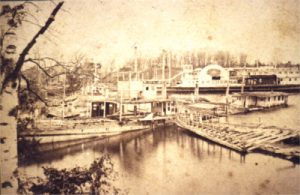

A working shipyard for 196 years (and counting), Shelburne Shipyard was first purchased for shipbuilding purposes by the Lake Champlain Steamboat Company in 1820. Between them and the Champlain Transportation Company, most of Lake Champlain’s passenger steamboats were built at this location, and a large number of them were retired in the older part of the shipyard once they had outlived their usefulness (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: A view of Shelburne Shipyard from the southern shore facing north ca. late 1850s. The retired, rotting hulls of Burlington (1837-1854) and Whitehall (1838-1853) have nowhere to go but down.

Among those that were retired in the Shipyard are the four steamer wrecks our crew investigated in 2014 and 2015. We believe these wrecks to be the remains of the steamboats A. Williams (1870), Phoenix II (1820), Burlington (1837) and Whitehall (1838) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: A satellite image of Shelburne Shipyard showing the four steamer wrecks. From left to right: A. Williams, Phoenix II, Burlington and Whitehall. (Bing Maps, 2013).

This year, the objective is to record cross section information from Wreck 2, or Phoenix II, in order to reconstruct what the steamer hull most likely looked like when it was retired in 1837. Wreck 2 has gone through several identity crises since the beginning of this project back in 2013, first thought to be either Franklin (1827) based on historical sources, then Winooski (1832), based on the length: the wreck was 133 feet long and Winooski was 136 feet long. Last year, when Dr. Crisman and I began recording sections, we realized the beam of the wreck at over 25 feet was much too large to fit the 20-1/2-foot beam of Winooski. After this realization, I spent the summer reading historical documents that might provide any clue to the identity of Wreck 2. Finally after much searching I found an enrollment paper for Phoenix II indicating the length was 143 feet, instead of the historically reported 150 feet found in the more ‘popular’ publications, making this steamer, with its beam of 27 feet, the most likely candidate for the identity of Wreck 2 (Fig. 4). It certainly didn’t hurt that Wreck 2 bore a remarkable resemblance to the wreck of Phoenix I (Fig. 5)!!

Fig. 5: Scaled site plans of Phoenix I (top) and stbd. side of Phoenix II (bottom). Both wrecks are similar in timber sizes and placements, and the overall lengths and beams are within just a couple of feet! (Top: G. Schwarz, 2012; Bottom: C. Kennedy, 2014).

Wreck 2, now believed to be the remains of Phoenix II, is an incredibly important archaeological site for several reasons. First of all, our knowledge of early steamboat construction is limited due to spotty historical documentation, and therefore the information we can glean from the archaeological evidence is some of the only information available for the time period between 1810 and 1850. Secondly, this wreck is a historically important, though rather grim, part of North American history, as it was the death-place of the first fatal cholera victim, a man named John Larned, on June 15, 1832. Larned boarded Phoenix II in St.-Jean-sur-Richelieu on June 14, 1832, after visiting a cholera hospital in Montreal, and 15 hours later, when the steamer arrived at its destination in Whitehall, New York, he was dying. This was all recorded in the diary of Captain Gideon Lathrop, master of the Phoenix II (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Portrait of Captain Gideon Lathrop (Stott, Peter. ‘Portrait of Gideon Lathrop (1805-1877). Columbia County Historical Society, Winter 2015, 30-38).

After Larned passed, nearly 150 people fell victim to the disease in the town of Whitehall, and the bacteria continued to travel south along the canals and waterways to New York City, where thousands died tragically over the course of the summer. Phoenix II, therefore, is responsible for bringing cholera into the United States, changing history forever.

The work we’re doing in Shelburne Shipyard is intended to call attention to the important role Lake Champlain’s steamboats had on early North American history, not only for the important events they were involved in, but how they themselves are examples of the changing technologies that are representative of and helped bring about the industrial revolution.

As we continue recording these wrecks, we would like to share with you some of the less scholarly, but more day-to-day aspects of this archaeological project. We are incredibly fortunate to have such a logistically easy and aesthetically beautiful working place, with great thanks to Mark Brooks and Charlie Tompkins for letting us stage our 12-14 person crew off their front yards (Fig. 7)!

The shale beach and shallow site, paired with the naturally protected harbor make diving a breeze – with 2-hour bottom times and minimal weather hazards our crew can get a lot of work done in a day.

For the most part, this wreck is an easy archaeological job. Most of it is exposed above the lake bottom, fairly well-preserved thanks to Lake Champlain’s cold, fresh water. Unfortunately for Chris Sabick, the LCMM’s archaeological director, the lower part of the wreck’s stern has disappeared behind tightly-packed clay. As it turns out, even underwater archaeologists should always keep a trowel handy (Fig. 8)!