By Matthew Magno

After hours of waiting, we finally found results on the fat content in some of the foods extracted from our supply that underwent 17th-century shipboard conditions in Galveston, Texas. More specifically, we applied the Soxhlet method to find out just how much fat was in the oatmeal, biscuit, and peas!

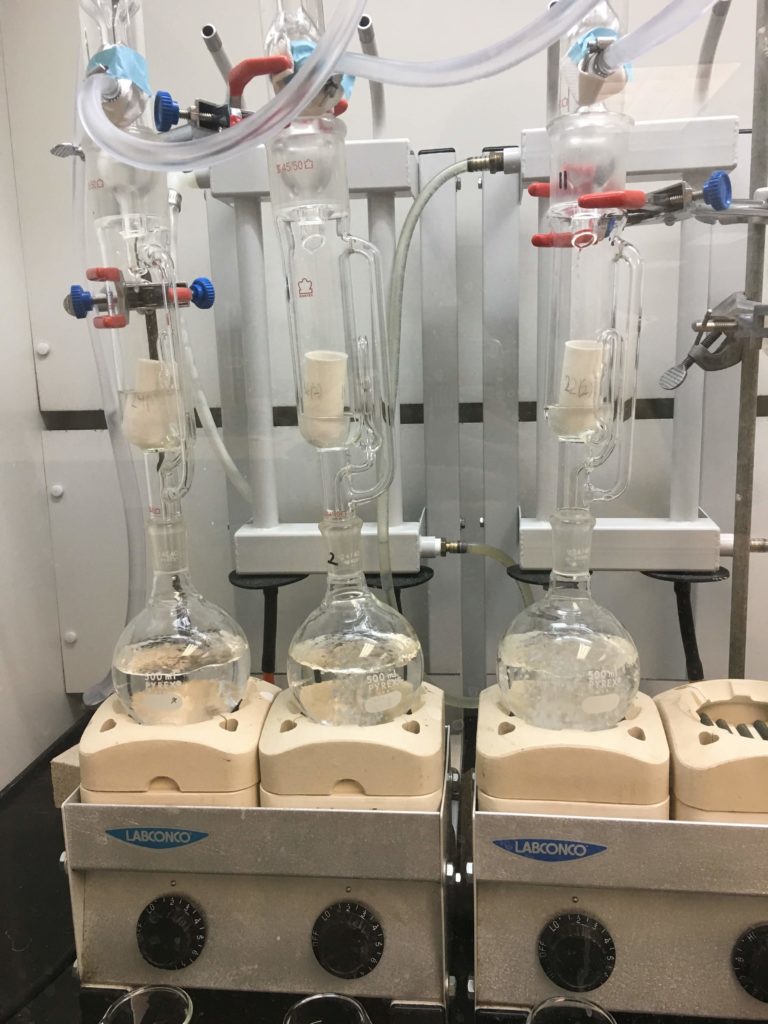

Soxhlet Apparatus

What is the Soxhlet method for those of you who may ask? The Soxhlet method is a scientific approach extracting lipids from compounds, and in this case, food. As depicted on the left, compounds set for extraction are placed in a thimble, and in some cases, steel wool is placed on top to prevent non-lipids from floating away. The thimble is then placed in the extraction chamber. An organic solvent, such as petroleum ether in this experiment, is placed in the flask (labeled ‘Boiling Flask’). The individual components – condenser, extraction chamber, and flask- are assembled to create the final Soxhlet apparatus.

Once assembled, the flask with the solvent is then boiled, allowing the solvent to volatilize (transition from liquid to vapor) and flow all the way up into the condenser. The vapor is turned back into liquid in the condenser and- with the help of gravity- falls into the extraction chamber and into the thimble. It is important to note that moderately cold water ran through the condenser the entire process to prevent the condensing chamber from warming up thus aiding the process of condensation (vapor turns into liquid on rather cold surfaces, per se). Because the organic solvent is non-polar just like lipids, the lipid dissolves and is diffused out of the thimble. Once enough solvent drops down into the extraction chamber, the solution in the chamber is transferred through the siphon arm and into the flask, periodically emptying the thimble and restarting the cycle again. This is continued for around six hours to ensure all the lipids have been extracted.

Method

All materials used, including the food, were dried to ensure that any water moisture would not affect the results of the experiment. Once done, the thimble was weighed each time material was added onto it (one for the thimble itself, the food sample, and steel wool). The extremely volatile petroleum ether was used as the organic solvent and each thimble was carefully placed into their own respective soxhlet apparatus in preparation for lipid extraction. The apparatus was transferred atop a ceramic hot plate, connected to a flowing cold water system, and run for approximately six hours. After six hours, we removed the thimbles from the extraction chamber and left them in the fume hood for twenty-four hours to allow the petroleum ether to evaporate. Finally, we placed them in the oven at 70ºC for another twenty-four hours to evaporate any moisture that built up.

Results

| Classification Number | Food | Thimble (g) | Thimble + Sample (g) | Thimble + Sample + Wool (g) | After Total (g) | Lipids Extracted (g) |

| 24 (1) | Oatmeal | 2.2205 | 5.538 | 5.6208 | 5.4133 | 0.2075 |

| 186 (2) | Biscuit | 2.1829 | 5.8176 | 5.8982 | 5.7510 | 0.1472 |

| 22 (2) | Peas | 1.9101 | 5.8537 | 5.9226 | 5.8152 | 0.1074 |

The table above provides the mass of the lipids extracted in this session as well as the food and material that came along with it in the process. Though there have not been direct comparisons to other foods’ lipid concentrations with what has been derived from this extraction, the end results give us a clearer outlook on the potential fat intake and clogged arteries of 17th-century sailors at sea.

Stay tuned for more fat- literally and figuratively- updates!