By Ruby Jean Velasquez

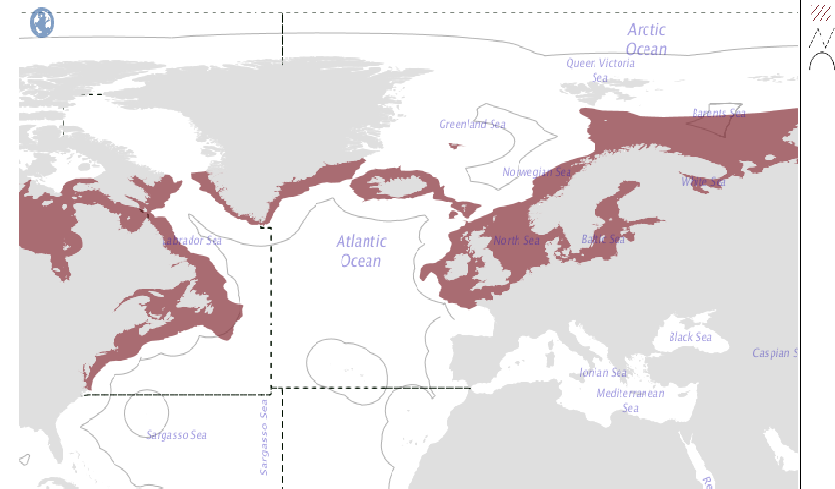

Atlantic Cod, Gadus morhua, is an omnivorous fish that dwells in the upper North Atlantic Ocean. Referred to as “the beef of the sea,” cod became the primary fish sought for after the discovery of Newfoundland by John Cabot in 1497. During the late 16th century, the cod fishing industry soared and the English began vying with the French, Spanish, and Portuguese over the fish trade. Finally, during the 17th century, the English launched their own cod market and became the primary fish suppliers to the Iberian Peninsula and early English colonists. Due to the multiple nations involved in the cod trade, various methods for preserving the fish were created.

Atlantic cod’s distribution stretches northward from the coast of North Carolina towards Greenland, and eastward along the coast of Ireland extending to some portions of Europe’s coastline (Image by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

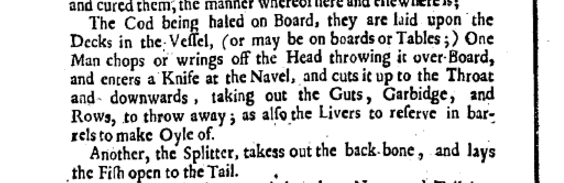

During the 17th century, the most common method the English used to preserve fish was referred to as the “Newfoundland” cure, however, other techniques such as brining, or pickling, were also used. The process of the “Newfoundland” cure involved beheading, dressing, splitting, lightly salting, and drying the cod before storage. In contrast, evidence suggests that brining involved soaking the entire cod in brine.

An excerpt from Salt and Fishery (1682) demonstrates how fish were dressed prior to salting. The process of the removal of the backbone is called splitting.

This curing information was then applied to data from the faunal remains found amid the wreckage of Warwick (1619) and Mary Rose (1545). Among Warwick’s faunal remains, 15 skeletal elements were identified as Gadus morhua. Of these identified bones, the spine and cranial findings were diagnostic because fish heads and backbones (spines) are usually removed during dressing and splitting. The presence of these bones infer that the cod aboard Warwick were brined. 31,793 fish bones were found aboard Mary Rose and over 90% of these bones were identified as Atlantic cod; however, unlike Warwick, no cranial specimens were found and 149 of the cod bones showed butchery marks, which are indicative of beheading and splitting the fish. The butchery marks suggest that the fish aboard Mary Rose underwent the “Newfoundland” cure, while Warwick’s cod were brined. It is possible that due to high humidity on ships, and the lack of opportunities for restocking on lengthy transatlantic voyages, the brined cod was preferable for stocking ships undergoing such journeys compared to naval ships that usually stayed close to European coasts.

Unfortunately, the sample sized used here is too small. More historical accounts and archaeological evidence are needed to form a definitive explanation as to why each method was utilized.